A Tale of Two Cities

Uptown & Downtown- Joined in Prosperity; Divided for Propriety.

Powered by the lumber industry and shipping, 1870’s Port Townsend became a critical port on the west coast. In those early days the commercial waterfront was awash with sailors, saloons, and girls. The port’s reputation was second only to San Francisco’s Barbary Coast for lawlessness.

Powered by the lumber industry and shipping, 1870’s Port Townsend became a critical port on the west coast. In those early days the commercial waterfront was awash with sailors, saloons, and girls. The port’s reputation was second only to San Francisco’s Barbary Coast for lawlessness.

Powered by the lumber industry and shipping, 1870’s Port Townsend became a critical port on the west coast. In those early days the commercial waterfront was awash with sailors, saloons, and girls. The port’s reputation was second only to San Francisco’s Barbary Coast for lawlessness.

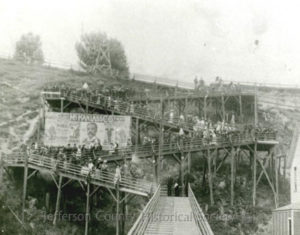

The early investors who made their fortunes on downtown’s industries created an enclave on the bluff, above the profanity and danger. They built family homes, churches, a Carnegie library, and a hospital. In those early days, the two communities were united by a long, zig-zagging wooden staircase and a cable car ascending the bluff at the end of Taylor street.

Jefferson Street was extended, cutting diagonally down the bluff, to connect the two communities. A set of stairs between Taylor and Jefferson Streets was installed to ease pedestrian access. The Haller Fountain was installed in 1893 at the base of the staircase.

A separate cozy village of shops and markets met the needs of the community’s entrepreneurs and more affluent tradesfolk. This allowed the ladies and children to escape the tumult of the commercial downtown when they wished.

Cutting back the bluff along Water Street using a steam engine and railroad cars. Isolated by the high bluff behind it, the downtown business district was made more accessible by blasting and hauling away sections of the bluff and building a street at its base and to uptown. (JCHS 1989.42.1)

Uptown had a startling level of artistic appreciation. The wives and daughters studied art from visiting European masters and they wore the latest fashions. The wealthy lived in the most contemporary homes. Meanwhile, downtown had not only dance halls, but the Learned Opera House which hosted international celebrities, traveling vaudeville, and home-spun productions.

A street scene at the corner of Water and Taylor Streets downtown, which includes a crowd, horses and wagons and the McCurdy building decorated with bunting. (JCHS 2003.134.280)

As Port Townsend aspired to be the Key City of Puget Sound, downtown became more refined with ornate stone and brick commerce buildings. A steam plant heated the buildings, Port Townsend Electric Company provided electric lights, even a telephone company.

The two communities were united with a long, zig-zagging wooden staircase and a cable car ascending the bluff at the end of Taylor street.

The Panic of 1893 saw Port Townsend’s population plummet from 9000 to barely 2000. Port Townsend Bay became a graveyard of abandoned boats. By 1900 the ships sailed by, headed for Seattle. Many Downtown buildings stood largely vacant while stately Uptown homes fell into ruin. In just 40 years, Port Townsend had sprouted, blossomed and faded. Owing to its relative isolation and the hard times that followed, much of the architecture remained unchanged for much of a century, allowing for its preservation when a new appreciation of the region’s history followed on the heels of a new wave of prosperity.

Learn More of Our History